2021.06.04.19

Files > Volume 6 > Vol 6 No 4 2021

Traditional practices in post-partum care among Indonesian and Filipino mothers: a comparative study

Marni Siregar*1, Sri Marasi Aritonang2, Juana Linda Simbolon3, Hetty WA Panggabean4, Robert H Silalahi5

Available from http://dx.doi.org/10.21931/RB/2021.06.04.19

ABSTRACT

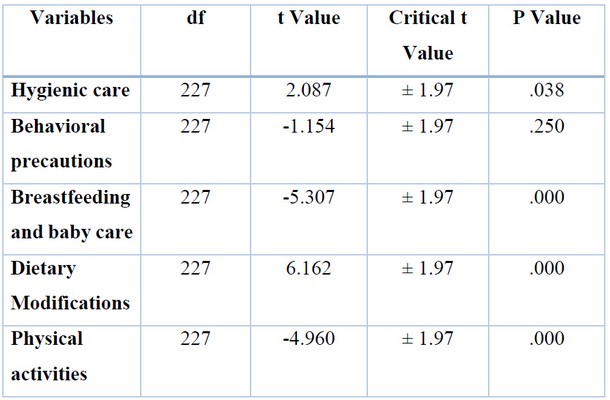

This study was conducted to assess the traditional practices in post-partum care among Indonesian and Filipino mothers to propose a program to improve maternal and child health. The study utilized a descriptive research design for Indonesian mother respondents (n=110) and Filipino mother-respondents (n=119) conveniently selected. Traditional practices on post-partum care focused on hygienic care, behavioral precautions, breastfeeding, baby care; dietary modifications; and physical activities. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage), weighted mean, and independent t-test were used to describe and analyze quantitative information. Four dimensions, including hygienic care (p-value 0.038); breastfeeding and baby care (p-value 0.000); dietary modifications (p-value 0.000); and physical activities (p-value 0.000), showed a statistically significant difference in the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care.

Meanwhile, the dimension on behavioral precautions (p-value 0.250) yielded statistically no significant difference on the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care. Four dimensions, including hygienic care (p-value 0.038); breastfeeding and baby care (p-value 0.000); dietary modifications (p-value 0.000); and physical activities (p-value 0.000), showed a statistically significant difference in the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care. Meanwhile, the dimension on behavioral precautions (p-value 0.250) yielded statistically no significant difference on the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care]

Keywords. Traditional; Practices; Postnatal Care; Cultural Diversity; Indonesia; Philippines

INTRODUCTION

There are many sources of variability in post-partum practices, both within and between cultural groups. Some traditional post-partum methods are based upon what we would consider supernatural or religious beliefs. Medical anthropology has long described health and illness belief frameworks in diverse cultures that include different ideas, such as religious, magical, or mystical beliefs1. Furthermore, the various health beliefs and explanatory models may vary depending on the observation level among the different social spheres of culture. Designated professional healers or medical practitioners may differ in their thoughts from folk healers, such as midwives, who may also differ from lay popular beliefs at large 2.

Traditional post-partum healing beliefs in South Asia are centered on the notion that a woman's body is drained of all its energy after birth. The mother must have complete rest and receive good nutrition to help restore vitality 3. For instance, many women from Indonesia and the Philippines continue to practice a wide range of traditional beliefs and practices during the post-partum period. Healing methods that have survived for centuries are still common practice and focus much attention on the recovery of new mothers 4. By recognizing and appreciating common local beliefs, care providers, primarily nurse-midwives, can better provide culturally competent care. Instead of reducing the choices available to women during the post-partum experience, providers should understand, respect, and integrate cultural interpretations of childbirth and women and their families 5.

Indonesian women's post-partum beliefs are grounded in religion and long-held health practices. Although the recommended reduction strategies are in place, the country is challenged with increasing maternal and neonatal mortality rates 6. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, post-partum recovery is also surrounded by a wide variety of beliefs, traditional practices, and rituals that involve both mother and infant. Cultural beliefs may be considered implementing maternal care and other health programs that fit their cultural practices 7.

In many societies in the Southeast Asian region, traditional beliefs and practices are believed to be vital to maternal and child health 8. Deep cultural and social meanings are attached to practices related to behaviors, activities, foods, hygiene, and infant care with variance by regions 9. There are pretty diverse interpretations of the traditional post-partum beliefs and practices, even in the urbanized communities 10. For example, in Indonesia and the Philippines, comparative post-partum mothers' beliefs and practices have not been well documented.

The Philippines is full of superstitions and beliefs regarding childbearing, mainly because Filipinos believe that there is nothing to lose if they abide with these beliefs derived from their traditions, customs, and culture. They emphasized that when a woman is pregnant, one foot is confined to a hospital while the other is bound 'six feet below the ground11. Similarly, in the Philippines, a low healthcare services utilization in post-partum women contributes to significant maternal deaths during the post-partum period 12.

The problem of morbidity or mortality in post-partum mothers is related to socio-cultural and environmental factors in the community. Many cultural practices harm public health behavior, resulting in a greater risk of infection13. In some cultures, abstinence from eating in pregnant women can affect nutritional intake14. The low level of community knowledge significantly affects maternal health15. In Nigeria, people with low knowledge will surrender to the gishiri incision, a vaginal surgery performed by traditional birth attendants in cases of obstructed labor16. Public perception of maternal mortality is largely colored by non-medical causes such as religion, beliefs, and supernatural factors17.

The purpose of this study is to compare the significant traditional maternal health beliefs and practices carried out by women during a post-partum stage in Indonesia and the Philippines with emphasis on influence on maternal health utilization].

METHODS

Design

This study utilized a descriptive research design that permitted an understanding of phenomena, meanings, and personal values in evaluating the traditional practices in post-partum care among Indonesian and Filipino mothers. Structured survey questionnaires were used to gather quantitative data. This approach afforded the collection of quantitative data about real-life experiences of Indonesian and Filipino mothers who have observed traditional post-partum practices passed on from one generation to another. Quantitative design generates a more rounded and objective understanding of phenomena (Hayes, Bonner, and Douglas, 2013). A descriptive approach was used for quantitative analysis, which will provide a clear interpretation of the traditional practices of post-partum care in which a cultural-sensitive care program may be developed to enhance maternal and child health.

Population, Sample, and Sampling Technique

The study population included Indonesian mothers from various localities of North Tapanuli, Indonesia, and Filipino mothers from different suburban districts of Manila. In determining the study sample, the researcher used convenience sampling to choose readily available subjects that the researcher believes are typical or representative of the accessible population. While the computation of sample size for this study was not required, a minimum of 100 Indonesian mothers and 100 Filipino mothers met the inclusion criteria such as conforming to traditional beliefs and practices in post-partum care and conveniently available in the selected research locales. In contrast, post-partum mothers with complicated pregnancies and over the post-partum stage are excluded from this study. Non-probability sampling was focused on a sampling technique where the selection of respondents was based on the judgment of the researcher based on the following inclusion criteria as Indonesian mother who conforms to traditional beliefs and practices in post-partum care, Filipino mother who conforms to traditional beliefs and practices in post-partum care, willing to participate voluntarily in the study.

Research Instruments

The research study referred to an open-access and validated tools on Postpartum Practices Survey by Shouman and colleagues of the Mansoura University of Egypt, designed to compare practices related to post-partum care and be modified to align with Indonesian and Filipino mother respondents.

The adapted self-administered survey questionnaire consisted of three parts: Profile Characteristics; Traditional Practices on Postpartum Care. Profile variables included age; marital status; education; religion, employment, and the number of children. Traditional practices on post-partum care focused on hygienic care, behavioral precautions, breastfeeding, baby care, dietary modifications, and physical activities. A four-point Likert scale was used to measure the responses. To identify the respondents' perspectives of the practices on post-partum care in two cultural settings, the modified instruments needed to be translated from English to Indonesian and back to the English language to ensure items in the questionnaire are properly adequately aligned with respondents originating from Indonesia and the Philippines. The content of the survey questionnaire in this study needed to be subjected to validation by some experts in traditional post-partum practices. All necessary recommendations by the experts were integrated into the internal organization of the research instrument to ensure all the items apply Indonesian and Philippine cultural background; a pilot study was done before conducting the main study to assess the reliability or validity of the data.

Furthermore, conducting a pilot enabled the participant's understanding of the questions and the timing required to complete the survey. The pilot study included 10 Indonesian and 10 Filipino mother-respondents who were not part of the actual survey. Internal consistency reliability was tested for each domain not just to examine the reliability and validity of the instrument but also to assess congruence with Leininger's Cultural Care Diversity and Universality Model that forms the theoretical framework of this study. The research instrument yielded an impressive overall 0.94 Cronbach alpha. An alpha value higher than 0.9, the internal consistency is excellent, and if it is at least higher than 0.7, the internal consistency is acceptable. (Richardson and Yu, 2015).

Data Collection Procedure

The researcher had initially secured approval from the Graduate School to conduct the study. The researcher further sought administrative approval from the local authorities in selected research locales included in the study. The researcher considered qualified Indonesian and Filipino mother respondents who were deemed principal participants in the study. After all approvals and permission had been secured, the researcher started screening eligible participants based on the inclusion criteria. The purpose of the study was carefully explained to all participants. Voluntary participation was clarified among the qualified respondents and written informed consent was obtained. Confidentiality of all gathered data was assured. Privacy and anonymity of the study respondents were maintained by eliminating all potential identifiers. The researcher had personally facilitated the distribution and collection of completed survey questionnaires and was around to answer any clarification from the respondents. Staff nurse respondents took approximately ten (10) minutes to complete the questionnaire. Completed self-administered questionnaires were immediately collected and checked for completeness by the researcher for analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage), weighted mean, independent t-test were used to describe and analyze quantitative information. Data collection was carried out between August 2019 and March 2020.

Ethical Considerations

The research study ensured the voluntary participation of the participants. Anonymity, confidentiality, and privacy of all gathered information from this study were maintained until the completion of the study. Moreover, the study, in general, adhered to all ethical standards conducted in the study. A cover letter was attached to the questionnaire to explain the details of the study. Written informed consent was obtained, and it was clarified to all participants that they were under no obligation to accomplish the survey questionnaire. All potential identifiers were eliminated in the questionnaire. The study's research protocol was subjected to the Ethics Review Board of the Trinity University of Asia.

Statistical Treatment of Data

In realizing the purpose of this study, the numerical data were treated utilizing the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software. Weighted mean was utilized for the assessment of Indonesian and Filipino mother-respondents on traditional beliefs and practices. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage), weighted mean, and independent t-test were used to describe and analyze gathered information]

RESULTS

[Results were extrapolated from questionnaires accomplished by the Indonesian mother-respondents (n=110) and Filipino mother-respondents (n=119) in this study. Data collection was carried out between August 2019 and March 2020.

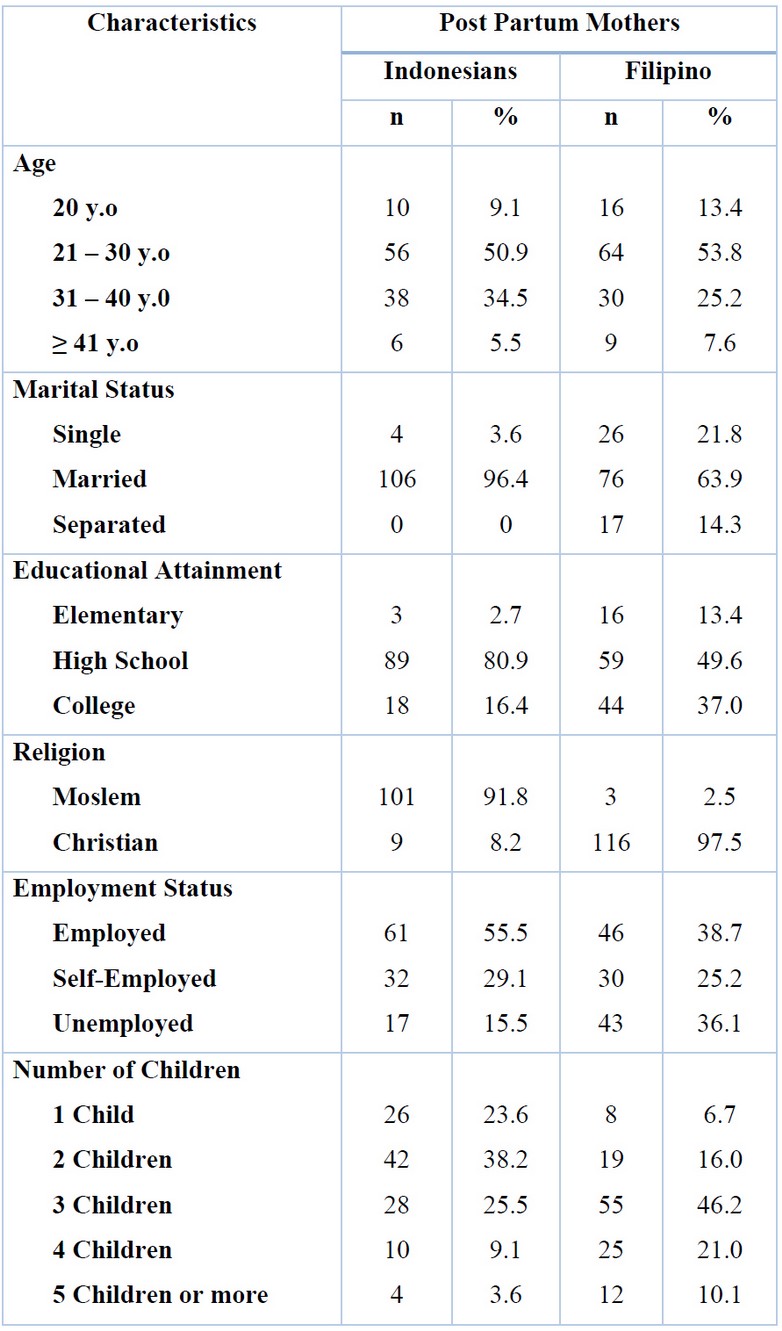

Table 1. Frequency Distribution of Respondent Characteristics

Based on the age characteristic, more Filipino mother respondents are 20 years old and younger (13.4%) than the Indonesian mother respondents (9.1%). However, more Indonesian mother respondents are between 31 and 40 years old (34.5%) than Filipino mothers (25.2%). According to their marital status, the more significant proportion of the mother respondents from both countries was married (Indonesian mothers, 96.4% and Filipino mothers, (63.9%). More Filipino mother respondents are single (21.8%) than the Indonesian mother respondents (3.6%). However, more Filipino mother respondents are separated from their spouse (14.3%) compared to Indonesian mother respondents (0%). More Filipino mother respondents finished college (37.0%) than the Indonesian mother respondents (16.4%). However, a minimal percentage of Indonesian and Filipino mother respondents have only reached elementary education with 2.7% and 13.4%, respectively. More Filipino mother respondents are unemployed (36.1%) than the Indonesian mother respondents (15.5%). Interestingly, about a quarter of the Indonesian and Filipino mother respondents are self-employed, with 29.1% and 25.2%, respectively. Moreover, more Filipino mother respondents had five children or more (10.1%) than the Indonesian mother respondents (3.6%).

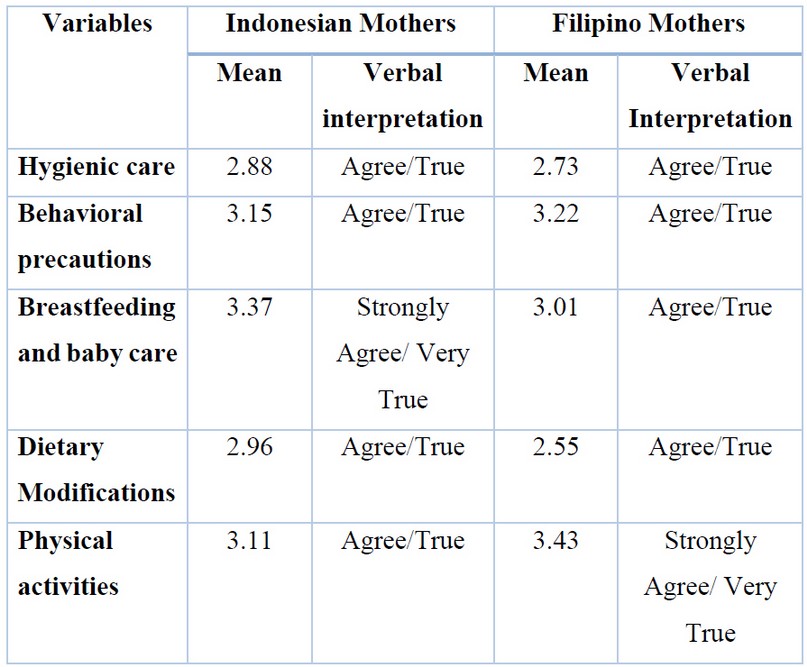

Table 2. The mean and verbal interpretation on the traditional Practices

Table 2 summarizes the assessment of traditional practices in post-partum care on the dimensions of hygienic care, behavioral precautions; breastfeeding and baby care; dietary modifications; and physical activities. With responses of mother respondents to the individual dimension ranging from agreeing to agreeing strongly, Indonesian mother respondents presented an Overall mean of 3.09 verbally interpreted as agreeing. In contrast, Filipino mother respondents depicted an overall mean of 2.99 verbally interpreted as agreeing as well.

For the majority of Indonesian mother respondents, the most notable dimensions of traditional practices in post-partum care pertain to breastfeeding and baby Care (x=3.37), behavioral precautions (x= 3.15), and physical activities (x= 3.11). However, the least notable dimensions refer to dietary modifications (x= 2.96); and hygienic care (x= 2.88). Meanwhile, for the majority of Filipino mother respondents, the most notable dimensions of traditional practices in post-partum care pertain to physical activities (x=3.43), behavioral precautions (x= 3.22), and breastfeeding and baby Care (x=3.01). However, the least notable dimensions refer to hygienic care (x=2.73); and dietary modifications (x=2.55).

Tablel 3. Difference between the Assessment of the Indonesian and Filipino Mother Respondents on Their Traditional Practices in Postpartum Care

Table 3 supports the analysis in determining significant differences in the assessment of Indonesian and Filipino mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care. An independent t-test was used to compare the five dimensions of traditional practices in post-partum care at a 5% significance level. Four dimensions, including hygienic care (p-value 0.038); breastfeeding and baby care (p-value 0.000); dietary modifications (p-value 0.000); and physical activities (p-value 0.000), showed a statistically significant difference in the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care. Meanwhile, the dimension on behavioral precautions (p-value 0.0250) yielded statistically no significant difference on the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care]

DISCUSSION

Hygienic Care

Assessment of two groups of respondents showed a congruent point of view about hygienic care in which they both strongly agree on regular cleansing of the breast to provide safe and most nourishing milk to the baby. Moreover, both cultures maintain cleanliness in the environment to avoid infection and avoid taking a cold bath after giving birth not to get chill but refrain from taking a bath with added herbs with medicinal properties to relieve aches and pains.

Traditional practices are standard in various cultures around the world, including Indonesia. Out of 1,331 ethnic groups currently living in Indonesia, around ethnicities still practice their local traditions 18. As early as 1961, anthropological studies described how a wide range of cultural ceremonies and traditions were performed by Javanese families connected with weddings, pregnancy, and childbirth. In the Timor communities of Indonesia, one common post-partum tradition is the Sei or smoke tradition, in which new mothers and their newborn babies sit or lie above embers from biomass fuel (e.g., wood and agricultural crop residue) for up to 40 days 19.

As regards hygienic care, Chinese women are advised to restrict bathing and hair washing during puerperium to prevent possible headaches and body pain in later years (You. 2015). Some women do not take showers during puerperium because they are fearful of cold. Many women add herbs to bathwater to smell aromatic as they believe that herbs promote wound healing 12. A similar study in Fujian Province, China, found that most rural mothers seemed to adapt to the tradition by bathing with boiled water with wine or motherwort herb (a familiar herb with medicinal properties) to prevent the problems of absorption through the skin. Wine and motherwort are both thought to have disinfecting properties and will therefore prevent infection. They believed that as they were with the baby, they needed to be clean to protect them from illness. It also made them feel comfortable and happy 3. Women also rub their bodies with herbs because they believe that rubbing helps uterine involution 20.

The use of an abdominal corset is every day among women to prevent pendulous abdomen 12. Most women perform perineal care by using water mixed with salt to prevent vaginal infection, promote wound healing, and eliminate unpleasant odours. In addition, slightly less than two-thirds of women used murr in painting their perineal wound and episiotomy sutures to promote healing. Some mothers in rural and urban areas wash their perineal area with boiled water and use iodine or alcohol to clean incisions or tears. Among the traditional practices among women is to take sitting baths, by putting on the floor of the container filled with boiling water and herbs are added to the water so that the genital area absorbs the plants' vapors, and after that, they sit in the water which is used to prevent vaginal infection 21.

Behavioral Precautions

Assessment of two groups of respondents showed commonalities in traditional practices regarding behavioral precautions where both cultures strongly agree on seeking help and support from their husbands, friends, family, and other relatives during the post-partum stage. Moreover, Indonesian and Filipino mothers limit reading, watching, or browsing on a computer or mobile phone to prevent eye strain; seek advice from parents, elderly and religious workers inspirationally; and focus on positive thoughts to keep them motivated during post-partum recovery. While Indonesian mothers stay inside the house and rest entirely within a month after delivery, Filipino mothers also adhere to this habit as a behavioral precaution.

In common sense, the protection period gains an essential meaning for women who respect the culturally learned standards and rules to avoid relapse due to complications resulting from inappropriate self-care. This action refers to the care human beings take of themselves through favorable practices to preserve their health. Numerous sources can influence women's preparation for adequate self-care during this period, including the health team, the media, and advice from mothers, grandmothers, and non-professional friends. Nevertheless, lack of orientation on the need for puerperal consultations upon discharge from hospital and professionals' lack of knowledge on the practices used in the home context can contribute to women's adoption of unhealthy conducts 22.

It should be reminded that it is in the domestic sphere that knowledge, decisions, and practices operate, which are sometimes conflicting with maternal health care needs. Therefore, it is fundamental for health professionals to get to know popular practices, encourage health promotion practices, and problematize harmful conduct that puts the well-being of the mother and child at risk. Studies reveal that puerperal women's major doubts relate to diet, bodily hygiene, physical exercise, and sexual intercourse. The belief in hypokalaemia emphasizes foods considered lactogenic, including canjica, milk, and rice pudding. Daily baths continue according to each woman's customs, but washing the head is prohibited during the protection period. Surrounded by meaning, the worst consequence of this practice is presented as death 23

Breastfeeding and Baby Care

Assessment of two respondents showed opposing views regarding placing religious articles on a baby's clothing to protect them from evil spirits. With the notion of protection from evil spirits, most Indonesian mothers embrace putting religious articles on their baby's clothing. On the contrary, most Filipino mothers do not follow the same practice 136 anymore. Nevertheless, both cultures showed commonalities in traditional practices regarding breastfeeding and baby care, particularly on breastfeeding their baby to provide the most nourishing milk; and protecting their newborn from anything that might harm them. Although Filipino mothers also apply baby oil or powder to their baby after giving a bath to provide warmth and comfort; and do not expose their baby outside late in the afternoon or when the mother feels the weather is cold, it is apparent that this kind of traditional practice is being performed by more Indonesian mothers in which they strongly agree.

Indonesia is one of many developing countries that continue struggling to improve children's and mothers' health outcomes. In Indonesia, infant mortality rates are highest among children whose mothers gave birth at age 40 or older, had high parity (3 or higher), and became pregnant after a short birth interval/less than 24 months. The rate is also highest for children living in rural areas, mothers with no education, and children in the lowest wealth index. According to the 2012 Indonesia Demographic Health Survey (IDHS), only one-third of Indonesian mothers follow WHO-UNICEF (2003) recommendation to provide breast milk only (exclusively breastfeeding practice) for the first six months of an infant's life. However, infants who take breastfed are generally breastfed until well into their second year or beyond, and the median duration of any breastfeeding is 21 months 24.

However, some women restrict water intake during the puerperium because of fear of water retention 25. In a study carried out in China, consuming a particular type of herbs during puerperium like Almjelb, Anise, hella is believed to facilitate lochial drainage, improve milk production, and expels cold the body, and mothers report that they consume more food than usual. The meals number ranged from five to eight in a day, starting at 5 am finishing with the meal before sleeping at night 26. There is a belief that post-partum women should eat much food because women are weak, and food will help rebuild their strength, promote recovery, and improve breastfeeding 3,27. Women consume food more than usual because they always feel hungry and to compensate for blood loss. Colostrum has been called mother's gold liquid, a thick, yellow substance produced toward the end of a female's pregnancy and is emitted by her mammary glands during the first 48 hours after giving birth 28.

Sadly, some women do not give colostrum to their babies, as they consider it insufficient and has no benefits for giving it to the baby. The women discarded the colostrum because it is dirty, "like pus," and potentially harmful to the baby 29. Women who know colostrum give it to their babies. In addition, more women have no intention to breastfeed their babies 30. Some women believe that they have a problem in milk production and breastfeeding increases breast size and body weight. The identified obstacles to breastfeeding are perceived milk insufficiency, maternal employment, breast and nipple problems, and pressure from family 31.

Dietary Modifications

Two groups of respondents showed opposing views on taking more hot soup with traditional vegetables to increase breastmilk production and eating more nutritious food to regain strength. Indonesian mothers both integrate taking hot soups and eating more nutritious food on their diets to increase breastmilk production and regain more strength. On the contrary, Filipino mothers do not apply the practices mentioned earlier in their dietary practice. Nevertheless, both cultures showed commonalities in refraining from eating foods that are thought not good for wound healing but follow recommended traditional diets advised by older female family members and avoid cold drinks while on post-partum recovery to prevent chill.

Mothers who have just given birth need good nutrition to support their healing and recovery. Furthermore, for mothers breastfeeding, their diet also directly impacts their baby's health and growth 32. Pregnancy takes an enormous toll on a women's body, and recovering from birth is a delicate and slow process that takes intention and support. Post-partum wellness has been misinterpreted as weight loss, but in actuality, a woman's body needs careful attention for recovery and healing in the form of nourishing foods, rest, and support 33,34.

In line with Garner's research, people in China believe that post-partum women are weak and lose energy and blood during delivery. For this, they should eat a lot of "warm" food full of proteins as this will help her regain strength, promote recovery, improve breastfeeding, enrich the blood, enhance recovery of the mother, facilitate discharge of lochia, and stimulate the production of breast milk.

Physical Activities

Assessment of two respondents showed commonalities in the traditional practice except that one group illustrates a higher degree of agreement over the other. More Indonesian mothers strongly agree with babysitting, bathing, and walking around the house, while Filipino mothers would also do the same on a much lesser consideration. Similarly, Indonesian practice avoids sexual activity while on post-partum recovery to avoid stress and infection, while Filipino practice also observes the same practice even more. Both groups of mother-respondents also avoid sexual activity while on post-partum recovery to avoid stress and infection; entertain occasional visits from friends, family, and other relatives; and get the body massage with aromatic or therapeutic oil or wear an abdominal corset to relieve pains and bleeding. Thus, both Indonesian and Filipino mothers traditionally adhere to physical activities that are essential to post-partum care.

In line with garner's research3 claim that all families believed that when the mother goes outside, wind will enter her body and cause illnesses not only arthritis and rheumatism later in life but also headache, poor appetite, and colds. They added that having adequate rest in the post-partum period helps the weak mother regain her strength and health to care for the new baby and resume normal activities. They regarded housework as a predisposing factor to the mother's exposure to either water or wind, causing arthritis and chronic aches.

Practices on post-partum and infant care are actions done by women and are not explained scientifically, but they continue to perform and are believed to be favorable to maintain their well-being since their mothers, mothers-in-law, and neighbors have practiced it and have guaranteed their health 35. For example, mother roasting 'can involve lying beside a stove for up to 30 days, squatting over a burning clay stove, sitting on a chair over a heated stone or a pot with steaming water, or bathing in smoke from smoldering leaves. These practices may be replaced by hot water bottles in Australia and placing a post-partum woman close to a heater. Post-partum women may be massaged with coconut oil to restore their lost health, expelling blood clots from the uterus, returning the uterus into a normal position, and promoting lactation. Some women perform various practices to dry out 'the womb36.

Limitations

Current research has not characterized all post-partum cultures in all corners of the country compared with the culture of post-partum mothers in the Philippines.

CONCLUSIONS

Four dimensions, including hygienic care (p-value 0.038), breastfeeding and baby care (p-value 0.000); dietary modifications (p-value 0.000); and physical activities (p-value 0.000), showed a statistically significant difference in the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care. Meanwhile, the dimension on behavioral precautions (p-value 0.250) yielded statistically no significant difference on the assessment of mother respondents on their traditional practices in post-partum care]

Acknowledgments

[We want to express our gratitude to the director of Poltekkes Medan for his support. We also appreciate the Dean of Trinity University for his kindness in providing support and mapping our research respondents]

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for this article's research, authorship, and/or publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declares no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Dennis C-L, Fung K, Grigoriadis S, Robinson GE, Romans S, Ross L. Traditional post-partum practices and rituals: a qualitative systematic review. Women's Health. 2007;3(4):487–502.

2. Gewehr RB, Baêta J, Gomes E, Tavares R. On traditional healing practices: subjectivity and objectivation in contemporary therapeutics. Psicologia USP. 2017;28(1):33–43.

3. Raven JH, Chen Q, Tolhurst RJ, Garner P. Traditional beliefs and practices in the post-partum period in Fujian Province, China: a qualitative study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2007;7(1):1–11.

4. Abad PJB, Tan ML, Baluyot MMP, Villa AQ, Talapian GL, Reyes ME, et al. Cultural beliefs on disease causation in the Philippines: challenge and implications in genetic counseling. Journal of community genetics. 2014;5(4):399–407.

5. Williamson M, Harrison L. Providing culturally appropriate care: A literature review. International journal of Nursing studies. 2010;47(6):761–9.

6. Organization WH. WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. World Health Organization; 2014.

7. Buser JM, Moyer CA, Boyd CJ, Zulu D, Ngoma-Hazemba A, Mtenje JT, et al. Cultural beliefs and health-seeking practices: Rural Zambians' views on maternal-newborn care. Midwifery [Internet]. 2020;85:102686. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102686

8. Morris JL, Short S, Robson L, Andriatsihosena MS oafal. Maternal health practices, beliefs and traditions in southeast Madagascar. African journal of reproductive health. 2014;18(3):101–17.

9. Wang Q, Fongkaew W, Petrini M, Kantaruksa K, Chaloumsuk N, Wang S. An ethnographic study of traditional post-partum beliefs and practices among Chinese women. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research. 2019;23(2):142–55.

10. Dennis CL, Fung K, Grigoriadis S, Robinson GE, Romans S, Ross L. Traditional post-partum practices and rituals: A qualitative systematic review. Women's Health. 2007;3(4):487–502.

11. Sioja. Philippine Beliefs on Pregnancy [Internet]. 10 April, 2012. 2021. Available from: https://knoji.com/article/philippine-beliefs-on-pregnancy/

12. Hishamshah M, bin Ramzan MS, Rashid A, Wan Mustaffa WNH, Haroon R, Badaruddin N. Belief and practices of traditional post partum care among a rural community in Penang Malaysia. The Internet Journal of Third World Medicine. 2010;9(2):1–9.

13. Bain LE, Awah PK, Geraldine N, Kindong NP, Siga Y, Bernard N, et al. Malnutrition in Sub–Saharan Africa: burden, causes and prospects. Pan African Medical Journal. 2013;15(1).

14. Yarney L. Does knowledge on socio-cultural factors associated with maternal mortality affect maternal health decisions? A cross-sectional study of the Greater Accra region of Ghana. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–12.

15. Kyomuhendo GB. Low use of rural maternity services in Uganda: impact of women's status, traditional beliefs and limited resources. Reproductive health matters. 2003;11(21):16–26.

16. Strand MA, Gramith K, Royston M, ... A community‐based cross‐sectional survey of medication utilization among chronic disease patients in China. International Journal … [Internet]. 2017; Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ijpp.12327

17. Royston E, Armstrong S, Organization WH. Preventing maternal deaths. World Health Organization; 1989.

18. Stern G, Kruckman L. Multi-disciplinary perspectives on post-partum depression: an anthropological critique. Social science & medicine. 1983;17(15):1027–41.

19. Poh BK, Wong YP, Karim NA. Postpartum dietary intakes and food taboos among Chinese women attending maternal and child health clinics and maternity hospital, Kuala Lumpur. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition. 2005;11(1):1–21.

20. Lo K. Postpartum Practices Among Combodian Mothers in Preah Vihear Provine: A Qualitative Study of Beliefs and Practices. Mahidol University; 2007.

21. de Boer H, Lamxay V. Plants used during pregnancy, childbirth and post-partum healthcare in Lao PDR: A comparative study of the Brou, Saek and Kry ethnic groups. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2009;5(1):1–10.

22. Cetinkaya A, Ozmen D, Cambaz S. Traditional practices associated with infant health among the 15-49 aged women who have children in Manisa. Journal of Cumhuriyet University School of Nursing. 2008;12(2):39–46.

23. Choudhry UK. Traditional practices of women from India: pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 1997;26(5):533–9.

24. La Aga, Erwin AL. Cakupan dan Determinan Pemberian ASI Ekslusif di Pemukiman Kumuh Dalam Perkotaan di Kecamatan Tallo Kota Makassar. Majalah Kesehatan FKUB. 2019;6(1):44–55.

25. Aaron S, Alexander M, Maya T, Mathew V, Goel M, Nair SC, et al. Underlying prothrombotic states in pregnancy associated cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurology India. 2010;58(4):555.

26. Lamadah SM. Post-partum traditional beliefs and practices among women in Makkah Al Mukkaramah, KSA. Life science journal. 2013;10(2):838–47.

27. Alifariki, L.O, Kusnan A, Binekada IMC, Usman AN. The proxy determinant of complementary feeding of the breastfed child delivery in less than 6 months old infant in the fishing community of Buton tribe. Enfermeria clinica. 2020;30:544–7.

28. Reotutar LP, Bermio JB. Beliefs and Practices During Pregnancy, Labor and Delivery, Postpartum and Infant Care of Women in the Second District of Ilocos Sur, Philippines. In: Proceeding Surabaya International Health Conference 2017. 2017.

29. Inayati DA, Scherbaum V, Purwestri RC, Hormann E, Wirawan NN, Suryantan J, et al. Infant feeding practices among mildly wasted children: a retrospective study on Nias Island, Indonesia. International breastfeeding journal. 2012;7(1):1–9.

30. Hamade H, Naja F, Keyrouz S, Hwalla N, Karam J, Al-Rustom L, et al. Breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, perceived behavior, and intention among female undergraduate university students in the Middle East: The case of Lebanon and Syria. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2014;35(2):179–90.

31. Organization WH. Management of breast conditions and other breastfeeding difficulties. In: INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. p. 65–76.

32. Wiessinger D, West DL, Pitman T. The womanly art of breastfeeding. Random House Digital, Inc.; 2010.

33. Goldstein RF, Abell SK, Ranasinha S, Misso M, Boyle JA, Black MH, et al. Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2017;317(21):2207–25.

34. Boardley DJ, Sargent RG, Coker AL, Hussey JR, Sharpe PA. The relationship between diet, activity, and other factors, and post-partum weight change by race. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1995;86(5):834–8.

35. Bermio J, Larguita E, Reotutar P, M Mathed R. Beliefs and Practices During Pregnancy, Labor and Delivery, Postpartum and Infant Care of Women in the Second District of Ilocos Sur, Philippines [Internet]. Vol. 8, International Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research. 2017. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320688971%0ABeliefs

36. Cabigon J. Use of health services by Filipino women during childbearing episodes. Maternity and reproductive health in Asian societies [Internet]. 1996;83–102. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/159583/filipino-preg-prof.pdf

Received: 16 June 2021

Accepted: 5 August 2021

Marni Siregar*1, Sri Marasi Aritonang2, Juana Linda Simbolon3, Hetty WA Panggabean4, Robert H Silalahi5

1,3,4Department of Midwifery, Health Polytechnic, Tapanuli Utara, Indonesia

2Department of Midwifery, Singaper Bangsa University, Karawang, Indonesia

5Department of Nursing, Health Polytechnic Dairi, Tapanuli Utara, Indonesia

Corresponding author:

Mrs. Marni Siregar

Departement of Midwifery, Health Polytechnic, Tapanuli Utara, Indonesia

Jamin Ginting St.

Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia 20137

+62 812-6261-995