2023.08.02.69

Files > Volume 8 > Vol 8 No 2 2023

False Positive Rose Bengal Test in COVID-19 Patients with Abnormal T3 And T4 Levels

Anam Aziz Jasim* 1

1. Lecture, Master in Biotechnology, Middle Technical University-Institute of Medical Technology, Al–Mansour, Baghdad, Iraq

Email: [email protected]

* Correspondence: e-mail@[email protected]

Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.21931/RB/2023.08.02.69

ABSTRACT

Brucellosis is a zoonotic infection that is quite frequent. Fever, weakness, sweating, especially at night, and joint discomfort are indications of brucellosis. COVID-19 symptoms are similar to those of brucellosis, which may cause a delay in identifying the latter. Objectives: The study aims to investigate patients with COVID-19 who test positive for Rose Bengal and who suffer from high fever, persistent joint pain, and fatigue, as well as abnormal levels of T4 and T3 hormone determination. 19 was detected in 90 patients (45 males and 45 females) between July 1 and September 20, 2020. The patients' ages ranged from 20 to 63 years. Laboratory tests were 2019-nCoV IgG/IgM COMBO test card, T4, T3, Rose Bengal Plate Test, C-reactive protein test (CRP), and total white blood cell count (WBCs). COVID-19 was detected in 90 patients (45 males and 45 females) between July 1 and September 20, 2020. All patients suffered from fewer white blood cells (less than 4000 cells\ cm3). The level of CRP protein was slightly higher in men than in women during the first week of infection, 40 (88.88%) and 35 (77.77%), respectively. At the same time, the T3 and T4 hormone levels in both sexes were less than expected in most patients. The levels of CRP protein in most patients at the beginning of infection were high (13.7-97 mg/L in both sexes. Five days after contracting COVID-19, a Rose Bengal test was performed on all patients. The highest incidence of brucellosis in COVID-19 patients was in the age groups 21-30 (38.18%) and 31-40 (34.54%), respectively. Doctors worldwide are concentrating on the COVID-19 epidemic. However, they must pay close attention to one crucial point: distinguishing COVID-19 from brucellosis to receive the proper therapy and recover quickly without any drug-related complications.

Keywords: COVID-19, brucellosis, Brucella abortus and SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

Brucellosis is a multisystemic zoonotic illness particularly prevalent in the Mediterranean and Central Asian nations. Fever, headache, sweats, anorexia, muscle and joint pain, weight loss, chills, malaise, and joint pain are all frequent brucellosis symptoms; osteoarticular involvement is joint in those with this disease 1, 2. The symptoms of COVID-19 are different and vary from mild to moderate, and they recover without entering the hospital. Some patient's life may end in death due to complications of the disease. The common symptoms include fever (38-39.5 °C), cough, fatigue, loss of taste or smell, inflammation of the mouth and pharynx, headache, pain in joints and muscles, diarrhea, rash, and red eyes. Severe symptoms in some patients include difficulty breathing, lung fibrosis, and kidney failure 3, 4. Most COVID-19 patients had an acute illness, and those who recovered had thyroid levels that were either normal or slightly lower than usual for T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine) hormones 1, 2, 3,4. As far as we know, no precedent reports describing co-infection with Brucella abortus and SARS-CoV-2. As such, the current study aims to investigate patients with COVID-19 who test positive for Rose Bengal and suffer from high fever, persistent joint pain, fatigue, and abnormal levels of T4 and T3 hormone determination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples Collection: COVID-19 was detected in 90 patients (45 males and 45 females) between July 1 and September 20, 2020. In several private Al-Karkh laboratories in Baghdad, venous blood samples were taken from individuals participating in the current study. All patients had a cough, fatigue, sweating, nausea, and fever (38-39°C). The patients' ages ranged from 20 to 63 years. Patients who contracted the virus for the second time and who were not vaccinated were selected.

Laboratory tests

Diagnosis of COVID-19 infection: 2019-nCoV IgG/IgM COMBO test card was used to diagnose SARS-COV-2 infection.T4 and T3 were estimated with Archem diagnostics kit, Turkey.Rose Bengal Plate Test: rapid slide agglutination test (Linear Chemicals S.L.U.; España). Seventeen days after treatment to recover from COVID-19, the Rose Bengal test was repeated on all patients, and the results were recorded. C-reactive protein test (CRP): is estimated with Archem diagnostics kit, Turkey. Total white blood cell counts 5.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as n (%). Data were analyzed using a statistical program (SPSS), and p-values were considered significant when <0.05.

RESULTS

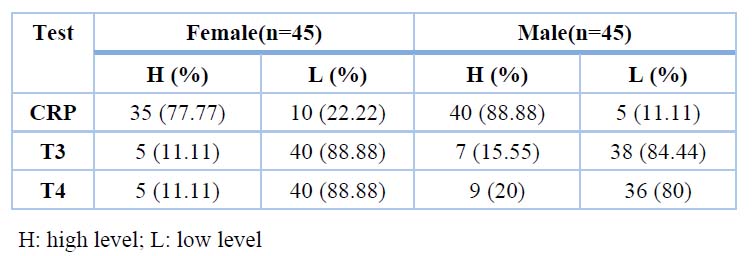

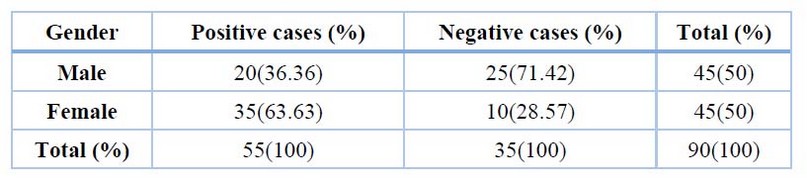

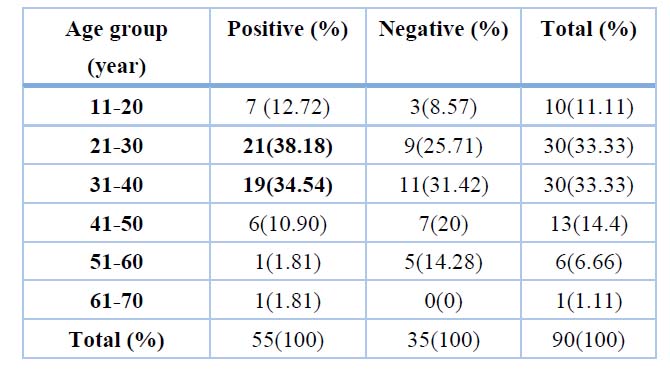

COVID-19 was detected in 90 patients (45 males and 45 females) between July 1 and September 20, 2020. All patients suffered from cough, fatigue, sweating, nausea, decreased number of white blood cells (less than 4000 cells\ cm3), and fever of 38-39 °C. The level of CRP protein was slightly higher in men than women during the first week of infection, 40 (88.88%) and 35 (77.77%), respectively. While the levels of T3 and T4 hormones in both sexes were less than average in most patients, as shown in Table 1. The levels of CRP protein in most patients at the beginning of infection were high; its value ranged between 13.7-97 mg/L in both sexes and after two weeks of infection and receiving treatment, CRP levels decreased to 9.1-13.7 mg/L. Five days after contracting COVID-19, a Rose Bengal test was performed on all patients. Seventeen days after taking the necessary treatment to recover from COVID-19, the Rose Bengal test was performed on all patients again, and the test results were negative. All patients had brucellosis titers from 1/160 to 1/320 [table 2]. The highest incidence of brucellosis in COVID-19 patients was in the age groups 21-30 years (38.18%) and 31-40 years (34.54%), respectively [Table 3].

Table 1. CRP, T3, T4 ratio in COVID-19 patients

Table 2. The percentage of Rose Bengal among patients with Covid 19, both female and male

Table3. Seropositivity of human brucellosis in patients with COVID 19 distributed in different age groups

DISCUSSION

Sometimes, the Rose Bengal test gives a false-positive result. Where the antigens used to prepare the kit are obtained from Brucella melitensis or Brucella abortus, most of these antigens are smooth lipopolysaccharide (S-LPS). The Rose Bengal test is used to detect immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the blood of infected people. However, one of the disadvantages of the test is that it lacks specificity to distinguish between false-positive reactions caused by other Gram-negative bacteria 6, 7. The results of the current study agree with the study of GemciogluI et al. in Turkey 8, where their results showed that the average age of the patients under study was 58.5 years and that 62.5 % were females. All patients (100%) of both sexes suffer from fatigue and fever, and the results of the Rose Bengal test were positive. In addition, the average CRP test was 24.5 mg/liter (89.5%).

Fatehi et al. (2020)9 found that a nasopharyngeal swab for reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction provides a more accurate diagnosis (RT-PCR). After one test, the number of false-negative tests might rise to as high as 33%. Also, the initial negative test should be repeated in epidemiologically suspected cases. CRP was 42 mg/L, lymphocytes 3.2 109/L, and ESR 72 mm/hr. The ferritin level in the blood was 271 ng/mL. The blood culture of a brucellosis patient was cultured with COVID-19 at the time of infection, and this patient had consumed raw camel milk two weeks before the infection and had been in direct contact with field animals. There were no signs of corona infection in the camels or the rest of the animals. The outcome of the Brucella titer follow-up serum was 1:10240 9. This case had a loss of taste, which is more common in SARS-CoV-2 cases and not commonly seen in brucellosis cases. The consistent lack of lymphopenia in COVID-19 is unusual. Lymphopenia was found in 35.3–82.1 percent of confirmed COVID-19 patients. However, relative lymphocytosis is a typical brucellosis result 10. Camels, in particular, are known to be intermediate hosts for MERS-CoV infection, while civets are recognized SARS virus mediators. SARS-CoV-2 is linked to bats and can infect people. However, the presence of an intermediary species for transmission has yet to be proved 11, 12, 13. COVID-19 was detected in the Turkish patient, who returned to the specialist four days later with persistent fever and joint pain. A second oropharyngeal swab sample was subjected to the PCR test. SARS-CoV-2 is not present. The patient's temperature was 38 degrees Celsius during his clinical evaluation. A serum C-reactive protein (CRP) of 2.6 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 32 mm/hr., and a white blood cell count (WBC) of 12,500 cell/mm3 were all measured in the laboratory. All other blood tests came out negative. The Rose-Bengal test was positive, as was the Brucella agglutination (Coombs antiserum) at a titer of 1/160 13.

In other studies, the laboratory results of an 18-year-old patient showed that the total WBC count was average (4.5 x 109/L) with a decrease in the platelet count (89,000/ mm3). The C-reactive protein concentration was elevated (66.54 mg/L), and the Rose Bengal test was positive. He was suspected of being infected with the Coronavirus; his swab appeared favorable for the PCR test, and after treatment, it appeared negative. The patient's blood culture resulted in brucellosis, and it was discovered that his family had a sheep farm and that his father had had contact with an aborted sheep fetus around 40 days prior 14. Following a single test, false-negative results might reach up to 33%. It is worth noting that a negative first test in epidemiologically suspected people does not rule out the diagnosis, and the test should be repeated 15.

The COVID-19 department has been assigned to the case of an 89-year-old Iranian man. Nodular opacities and lung infections were discovered on a chest computed tomography scan. His findings also revealed that he suffered from active brucellosis even though both SARS-COV-2 and serological tests were negative. The patient had been infected with Brucella eight years after consuming raw milk from a dairy farm. Brucella symptoms reappeared before getting infected with Covid 19. After a follow-up serum (IgM/IgG) indicated a positive Brucella titer of 1:160 for Wright and 1:160 for Brucella Coombs Wright, the patient was diagnosed with active brucellosis 16. Respiratory involvement with brucellosis, on the other hand, is uncommon and primarily documented in case reports. SARS-2 infections are more likely to cause diarrhea, whereas brucellosis is more likely to cause drenching perspiration.

Furthermore, our case had a loss of taste, which is more common in SARS-CoV-2 and not commonly seen in brucellosis. Lymphopenia was detected in 35.3–82.1% of confirmed COVID-19 patients 17, but in contrast, relative lymphocytosis is a common finding in brucellosis 18,19,20,21. Because several of our patients live in the country, some medical histories included exposure to animals such as sheep and ingesting unpasteurized milk. This is a rare brucellosis and COVID-19 report that we are aware of.

CONCLUSIONS

Doctors from all across the world are concentrating their efforts on the COVID-19 epidemic. However, they must pay close attention to one crucial point: distinguishing COVID-19 from brucellosis to receive the proper therapy and recover quickly without any drug-related complications.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology (DHCPP); November 12, 2012; https://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/symptoms/index.html.

2. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), Division of Viral Diseases, February 22, (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html.

3. Taghreed Khudhur Mohammed and Anam Aziz Jasim. 2021. Food and Nutrition Safety During the COVID-19 pandemic; AJMPS; Issue (0) – February.

4. Abed Jawad Kadhum; Taghreed Khudhur Mohammed; Salwa H. N. Al-Rubae'I; Ali Shallal Alabbas; Mohammed Abed Jawad and an elite group of Arab and Iraqi researchers and academics, 2021. Educational articles for COVID-19; First edition, Publisher: Al-Nisour University College, Iraq.

5. Clinical lab tests and health, White blood cell: Part 2 – Total Leukocytes Count Procedure, TLC Solution Preparation. 2021. https://labpedia.net/white-blood-cell-part-2-total-leukocytes-count-procedure-tlc-solution-preparation/

6. Muñoz PM, Blasco JM, Engel B, et al.. Assessment of performance of selected serological tests for diagnosing brucellosis in pigs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol.; 2012, 146(2):150-8. PMID: 22445082; DOI: 10.1016/j. vetimm.2012.02.012.

7. Corbel MJ. Brucellosis in humans and animals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/resources/ publications/Brucellosis.pdf?ua=1. Accessed in 2020 (August 25).

8. Gemcioglu Emin, Erden Abdulsamet, Karabuga Berkan, Davutoglu Mehmet, Ates Ihsan, Orhan Kücüksahin, Rahmet Güner. False positivity of Rose Bengal test in patients with COVID-19: case series, uncontrolled longitudinal study LETTER TO THE EDITOR, https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2020.0484.03092020; Sao Paulo Med J. 2020; 138(6):561-2.

9. Fatehi Elzein, Nisreen Alsherbeeni, Kholoud Almatrafi, Diaa Shosha, and Kaabia Naoufe. COVID-19 co-infection in a patient with Brucella bacteremia, Respir Med Case Rep.; 2020, 31: 101183. DOI: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101183

10. Parry N.M.A. COVID-19 and pets: when pandemic meets panic. Forensic Sci Int Rep. 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100090

11. Ye Z.-W., Yuan S., Yuen K.-S., Fung S.-Y., Chan C.-P., Jin D.-Y.. Zoonotic origins of human coronaviruses. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, DOI: 10.7150/ijbs.45472.

12. Abed Jwad Kadhum; Taghreed Khudhur Mohammed; Salwa H. N. Al- Rubae'I; Ali Shallal Alabbas; Mohammed Abed Jwad; et al. 2021. Educational articles for COVID-19, First edition, Publisher: Al-Nisour University College.

13. Güven Mehmet. Brucellosis in a patient diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), J Infect Dev Ctries; 2021, 15(8):1104-1106. doi:10.3855/jidc.13899.

14. Kucuk Gultekin Ozan and Gorgun Selim. Brucellosis Mimicking COVID-19: A Point of View on Differential Diagnosis in Patients with Fever, Dry Cough, Arthralgia, and Hepatosplenomegaly, Cureus; 2021, 13(6): e15848. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.15848

15. Wikramaratna P., Paton R.S., Ghafari M., Lourenco J. 2020. Estimating false-negative detection rate of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. MedRxiv. DOI: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20053355.

16. Shiva Shabani and Saleh Ghadimi, 2022. COVID-19 co-infection in a patient with brucellosis. DOI: 10.22541/au.164931667.79419523/v1 .

17. Kim D., Quinn J., Pinsky B., Shah N.H., Brown I. 2020. Rates of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. JAMA.;92 DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.6266.

18. Nickel C.H., Bingisser R. 2020. Mimics and chameleons of COVID-19. Swiss Med. Wkly. DOI: 10.4414/smw.2020.20231.

19. Solera J, Solis Garcia del Pozo J.. Treatment of pulmonary brucellosis: a systematic review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther.; 2017, 15:33–42.

20. Ali, A. F., Mohammed, Th. T. & Al-Bandar, L. K. 2019. Effect of adding different levels of Optifeed®, Vêo® Premium and Oleobiotec® to the diets as appetite stimulants in the production and physiological performance of Male broiler under heat stress conditions. Plant Archives, 19(1): 1491-1498.

21. Galińska EM, Zagórski J.. Brucellosis in humans–Etiology, diagnostics, clinical forms. Ann Agric Environ Med.; 2013, 20:233–238.

Received: May 15, 2023/ Accepted: June 10, 2023 / Published: June 15, 2023

Citation: Jasim A A. False Positive Rose Bengal Test in COVID-19 Patients with Abnormal T3 And T4 LevelsRevis Bionatura 2023;8 (2) 69. http://dx.doi.org/10.21931/RB/2023.08.02.69